I noticed several interesting patterns when I was viewing the wage and ethnicity maps provided on moodle. Specifically, there appear to be large areas that are primarily one or ethnicities, and it is rarely the case that a household of one ethnic group is not located near another household of the same ethnic group. I will comment on how this reflects the connection between ethnic identity later in this post, but I wanted to first focus on a comparison between the ethnic composition of these particular neighborhoods and the reported wage rates in these areas.

It was quite interesting to see that there did appear to be a strong connection between ethnicity and reported wage rates in these particular neighborhoods. A quick side-by-side comparison of the wage and ethnicity maps shows that there are certainly aggregations of individuals earning similar amounts of money, and this is certainly not a surprise; generally people try to live around individuals who are of the same socioeconomic status. However, if this wage map were to be superimposed on the ethnicity maps, one would see that the areas reporting higher wages were also from similar ethnic backgrounds (specifically the English, Polish, Bohemian, and Russian groups). This same trend is startlingly true for the poorer areas as well, as the lowest wage reporters ($0-$10) were found in a large group in region 33 of Map 1. This group was predominantly Italian. I find this connection quite interesting, as we studied this particular cultural phenomenon in AP US History. Specifically, “new” immigrants who were not as well established socioeconomically were paid lower wages than “older” immigrant groups who had been in the region for longer.

As I briefly mentioned earlier, there appear to be specific areas in the ethnicity maps where one ethnic group basically is predominant. This is seen on Bunker and Ewing street, where the ethnic composition is primarily Bohemian and Italian, respectively. There are many possible reasons for this, but I would like to propose one possible mechanism that Professor Smith discussed earlier this year. When Professor Smith was discussing his documentary, Islam in America, he noted that neighborhoods such as the Islamic one in Dearborn, MI can arise as groups of immigrants come to America together. The first group generally starts living together, either by choice, economic pressures, or worker housing. This in turn creates a support network, and subsequent immigrants may gravitate towards this particular neighborhood, either due to family connections or simply overall comfort. This creates aggregations of certain ethnic groups, and this trend is still quite visible today (think Chinatown, Little Italy, etc.)

The final question in the blog prompt asks us to determine if there is any common space where people might intermingle. From the maps that I looked at, it appears that the housing is quite cramped and that there is little room for streets, much less common areas where ethnic groups might intermingle. This hypothesis is supported by Jacob Riis’s work, which depicted the harsh cramped conditions that offered no place for children to play, much less larger communal areas. Even Jane Addams comments on this lack of space, and I don’t think it would be a stretch to assume that the cramped residential areas would be primarily constructed to maximize potential housing units for tenants. This lack of public areas may have contributed to the aggregation of certain ethnic groups seen particularly in Maps 1+4, because a lack of public areas of interaction would certainly slowed the cultural assimilation of these various ethnic groups. It is interesting to note that whether by choice or environmental pressures, people generally create well-defined borders for themselves.

Tuesday, June 3, 2008

Friday, May 30, 2008

Additional Post: Dawkins vs. Ridley vs. Miller

I recently had a chance to wrap up an independent term-long project, and the connections between my subject of interest and religion were simply too enticing to pass up. This year in Freshman Studies we were supposed to (I included supposed to because some people didn’t) read Matt Ridley’s The Agile Gene. This book is essentially a compilation and brief extension of primary and secondary scientific source material. Given my own interest and focus in the natural sciences, I was curious as to how this book got onto the Freshman Studies syllabus. I asked a professor, and I was told that The Agile Gene had replaced a (supposedly) similar book, Richard Dawkins’ The Selfish Gene. I had heard of this Dawkins character before, and being the curious and inquisitive scientist that I am, I had to read this work. I was somewhat struck by Dawkins’ “religious atheism”, as Professor Maravolo described it, and I will touch on this subject later, but I found the work to be almost unscientific in the way its arguments were constructed and presented. At the recommendation of two of my professors, Beth De Stasio and Nicholas Maravolo, I read a third book, Kennith Miller’s Finding Darwin’s God. Miller’s book provides an interesting argument that is a good contrast to the absolutes presented by Dawkins in The Selfish Gene. A comparison of these three texts prompted me to think about the relationship between the cultures of science and religion and how they are so often simultaneously intertwined and at odds with eachother.

Kennith Miller makes a valid point when he claims that both religion and science attempt to construct frameworks through which we interpret and assign meaning to existence. Given that science and religion often arrive at separate explanations as to why things occur/have occurred, it makes sense that there is often conflict between the cultures of science and religion. One doesn’t have to look far to find the byproducts of this cultural warfare; upset by the scientific claim that the earth is billions of years old (this is in conflict with their accepted Canon), Young Earth Creationists have reinterpreted and created scientific theories to explain their beliefs in a manner that is quite similar to the way that religions reinterpret themselves. Dawkins makes a clear argument in The Selfish Gene that this sort of thinking is foolish and pointless; according to Dawkins, we should simply disregard conceptual frameworks that are apparently wrong, even if they are useful and practical for some people (i.e. comfortable and conducive to a better/more fulfilled existence). Miller takes an opposite approach and argues that science and religion are not mutually exclusive; although there are obviously contradictions between some religious texts and currently accepted scientific knowledge, we can use our current knowledge to expand our understanding and appreciation of our religious beliefs instead of focusing on the contradictions and points of conflict(an almost Augustinian way of approaching the science vs. religion argument).

Given that science and religion both provide answers to one of the larger human questions (Where did I come from?) it makes sense that there is sometimes a conflict between the two. I was slightly bothered by Dawkins’ The Selfish Gene when I read it, as he almost seems to be pushing his own religion (if we can call atheism a religion) on his readers while he simultaneously criticizes the religious beliefs of others. I’m glad that I had a chance to read Kennith Miller’s Finding Darwin’s God as well, as it provided a nice contrast to Dawkin’s work; Miller’s argument that the different conceptual frameworks of religion and science are not mutually exclusive was well constructed and beautifully written. I don’t particularly agree with what any of the three authors argue, but I think it is interesting to note that individuals are capable of interpreting seemingly unbiased scientific information into their own conceptual frameworks for existence. As a student-scientist, I think that an awareness of this phenomena is paramount, and I’m very glad I had a chance to read these books in conjunction with taking Rlst 100.

Thursday, May 29, 2008

Finding Religious Content in the Social Work of Jane Addams

For this week’s blog we have been prompted to analyze the religious content of the social work instituted by Jane Addams. Although it is difficult to directly connect religious meaning with social action, I intend to show that the work of Jane Adams was profoundly influenced by her Quaker upbringing and the conceptual framework which it instilled upon her. Much of the first chapter in Jane Addam’s book, Twenty Years at Hull House, focuses on her admiration for her father, John H. Addams. Passages like, “My great veneration and pride in my father manifested itself in curious ways. On several Sundays, doubtless occurring in two or three different years, the Union Sunday School of the village was visited by strangers...I imagined that the strangers were filled with admiration for this dignified person, and I prayed with all my heart that...[I] would never be pointed out to these visitors as the daughter of this fine man” (7) make it clear that Jane Addams idolizes her father and the way that he lives his life.

The difficulty of finding religious content in the social work performed by Jane Addams is that the work itself was not presented as a religious project. The primary goal of the Hull House was to save and improve mortal human lives, not souls, and Jane Addams does not seem to focus on conveying a religious message to the people that she is helping. I found this slightly strange, but I did a little bit of extra research and found that many of the ideas and ideals that Jane Addams preached were actually against the social norms of her time, including cultural feminism, women’s suffrage, and social pragmatism. Given her unorthodox views for the time, it makes sense that Addams would have established an institution that was not directly affiliated with the church, but this certainly doesn’t mean that her actions and beliefs were not influenced by religious teachings, consciously or not.

Many of the Quaker teachings that Jane Addams reflects fondly upon in Twenty Years at Hull House are apparent in the social work that she instigated. I think the most striking example of this is the almost fable-like story that Jane Addams recounts when she is thinking about her interactions with her father. Jane Addams writes that she had recently received a beautiful article of clothing and she wanted to wear it to church, but her father suggested that she wear a more plain cloak. His reasoning behind this was that a fancy cloak might make other girls feel bad, and this is a wonderful encapsulation of the Quaker ideal of a community of equals. It is readily apparent that Jane Addams was trying to improve the living conditions for individuals who were from less privileged backgrounds. Although Jane Addams did not portray her social work as religious, I think that many of the social ideals of equality and philanthropic leanings of Addam’s were directly due to the religious influence on her childhood. This may not be blatantly religious in nature, but if we are to assume that religions are simply systems of symbols, what better symbol than an esoteric set of thoughts or values? Religions act on individuals in ways that create conceptual frameworks through which we view the world, and although I am not an explicitly religious person, I recognize that my upbringing instilled certain religious ideals on my thought processes. With this in mind, I would argue that the work of Jane Addam’s certainly bears the mark of a Quaker’s religious mind set, and because of this it has religious content.

Friday, May 23, 2008

Damian Marley's "Road to Zion"

Many people recognize Bob Marley as the most influential and successful reggae artist of all time, and he certainly deserves this honor. However, reggae music is certainly not a genre that is defined or even inspired by one singular artist; there were many influential reggae bands before Bob Marley and the Wailers, and reggae itself changed throughout the course of history as a reflection of the cultural and social conditions that fostered its emergence. Much like many religions, reggae music has continued to change in response to the environment it interprets. I recently had a chance to hear a song by Damian Marley, one of Bob Marley’s children, that nicely encapsulates this peculiar aspect of reggae music. The song is called “Road to Zion”, and the music video for the song can be found by clicking here.

The first thing that struck me about this song was Damian Marley’s lyrics and the overall structure/backing beat of this song. Unlike much of Bob Marley’s work, this song seemed to have a straight four-count beat with none of the off-beat rhythms that one traditionally associates with reggae music. Furthermore, the “melody” for this song is comprised of a piano riff that is much more characteristic of Nas’s earlier work on Illmatic than Bob Marley’s distorted guitar, smooth basslines, and pulsating keyboards. These differences didn’t really make sense until I looked at the lyrics; much of Damian’s lyrics are based on traditional Rastafarian ideas and conflicts (Clean and pure meditation without a doubt/Don't mek dem take you like who dem took out/Jah will be waiting there we a shout/Jah will be waiting there!), but a significant portion of his verses seem to comment more on current issues (Media clowns weh nuh know bout variety/Single parents weh need some charity/Instead of broken dreams and tragedy/By any plan and any means and strategy). There were certainly elements of both rap and reggae music in this song, but it wasn’t until I watched the music video that I really understood the meaning of this crossover.

In the music video for Damian Marley’s “Road to Zion” there is plethora of Rastafarian symbols, ranging from the Ethiopian colors to the bible. However, there is also a strong element of inter-city living/rap aesthetic found in this video. This is primarily brought out by Nas, who has a verse in this song and plays a role in the music video. However, two of Damian’s lines really struck me as un-Rastafarian: (Bust of trigger finger, trigger hand and trigger toe/A two gun mi have mi bust dem inna stereo). These lines are really a step over into the gangster rap genre that I had certainly not anticipated. There are definitely aspects of Rastafarian culture and music in this video (after Nas is captured and put in “prison”, Damian “frees” him by giving him a postcard with the lion of Judah on it, and he has a cart of books that he distributes to other prisoners), but these are often muddle with elements of rap that are sometimes in conflict with the original Rastafarian ideals. However, for individuals living in America and dealing with different forms of oppression, perhaps this music and imagery is a more fitting interpretation of their experiences. Damian Marley is certainly catering to a different audience with this style of music, but I find it interesting to see all the various aspects of Rastafarianism and reggae that have been reworked to fit another style of music geared at a radically different demographic- modern American consumers of rap culture. Much like religions reinterpret themselves as time progresses, the music of reggae has seemingly found a way to reinvent itself and establish a niche in the popular music market of today.

Monday, May 19, 2008

Rastafarian Documentary: La Orden Boboshanti

After reading several chapters of Rastafari, I was prepared to see anti-establishment feelings and ideas expressed in a Rastafarian community, but the shanty town depicted in the Youtube video (La Orden Boboshanti) was initially unexpected but ultimately appropriate, given our readings. I would say that my initial surprise primarily stemmed from my previous perspective and exposure to Rastafarianism. Specifically, Edmonds’ book, Rastafari, prepared me for a community of individuals who have rejected the norms of society and are strong and confident in their cultural heritage and religious beliefs. However, I got the impression that many individuals, even entire Rastafarian communities, still resided in urban areas, and I was not prepared to see an entire community of Rastafarians living off the land. However, after some reflection I began to realize that these unexpected characteristics of the Rastifarian community were not really that far-fetched, and that many of the aspects of Rastafarianism portrayed in Edmonds’ book were spot-on.

Perhaps most interesting and appropriate theme that I identified in this short film was the sense of separation from traditional society that this society conveyed. This entire community appears to be surviving via alternative means, both living off the land and profits from broom sales. This certainly seems like a good way to escape the “downpression” of western society and freely practice religious and cultural beliefs as a community. Furthermore, there were many symbolic representations in this community, many of which were predicted in Edmonds’ text. For example, an entire building was painted the colors of the Ethiopia, and most individuals wore a crown-like head covering. I found it extremely interesting to note that on one of the signs there was a picture of a black R over a white X, seemingly signifying the superiority of the black (good) over the white (evil). Given the potential racial exclusion and tensions that arose as a byproduct of cultural oppression, I did not find it surprising to see this expressed in a symbolic nature in this particular community.

Prima facie, this does not appear to be what one would traditionally associate with a Rastafarian community. However, in light of Edmonds’ writing on Rastafarian religion and culture, many of the things observed made perfect sense. Although an entire community rising at 3 AM to pray may seem un-Rastafarian and perhaps even cult-like in its behavior, this makes sense when one views Rastafarianism in the way that Edmonds’ presents it; it is an earnest system of beliefs and symbols that arose in a certain group of peoples as a result of cultural and social pressures. I feel that too often Rastafarianism is viewed as simply a lifestyle or personal choice. This may be true for some individuals, but for many people it is an actual religion that can permeate virtually all aspect of one’s life. In light of this consideration, I think it would be practical to re-evaluate our perceptions of Rastafarianism and consider it as a legitimate religion, as it certainly is constructed with a unique framework through which a group of people interpret their experiences.

Thursday, May 15, 2008

Additional Post: Islam in America Documentary

I had a chance to attend Professor Smith’s documentary on Islam in America on Monday. I found his documentary to be fairly interesting, and I especially liked how he compared two different acclimation responses of Islam to American culture, specifically in Dearborn, MI. The contrast of Muslim individuals living in a fairly close-knit community with that of a more Americanized version of Islam (what Professor Smith referred to as the mega-churching of Islam, complete with Starbucks) was a helpful comparison. I think this clearly demonstrates that there are various ways for religion to respond to external pressures, and even in a small community like Dearborn, MI there are multiple ways that a religion can be interpreted to best suit the situation of its followers.

The one portion of the presentation that I was slightly confused with was the question and answer session. Many of the students seemed to focus on the potential exclusion or discrimination that was mentioned in Professor Smith’s documentary. Although I’m sure Professor Smith meant to include these accounts as a way of showing the kinds of obstacles that Muslim-Americans have had to overcome, I’m not entirely sure that this was a central point that Professor Smith was trying to make. To me, it seems that many students zeroed in on this portion of the documentary and missed out on the larger themes that this film conveyed, specifically how a religion acts as a dynamic institution that is simultaneously affecting and being effected by its environment. This may be a byproduct of the so-called lense that Lawrence instills upon its students, but I was slightly disappointed that more individuals didn’t latch on to some of the more overarching topics that Professor Smith touched on in his documentary. Overall, I found the documentary to be interesting, informative, and funny (there were few chuckle-worthy moments interspersed throughout), and I’m glad I had a chance to attend.

The parallels between Mormonism and early Ethiopian Christianity

When we were discussing the process by which Ethiopian Christians associated themselves with Israel, the story of the Kebra Negast seemed oddly familiar to me. Although we have studied the way that several religions have reinterpreted themselves throughout time, the specific comparison that came to mind was Mormonism. I did a bit of online research, and the parallels that I found between Mormonism and early Ethiopian Christianity were fairly astounding.

We have already talked through the assigned reading of the Kebra Negast in class, so I will not take up space summarizing the story, but I would like to restate the function that the Kebra Negast served for early Ethiopian Christians: by establishing a strong link to King Solomon, arguably the strongest Christian leader of Israel, early Ethiopian Christians legitimized their claim as a Christian center. In turn, this likely piqued the interest of non-religious individuals and created a stronger sense of solidarity within the Christian community of Ethiopia at that time. By reinterpreting and adding to preexisting stories, early Ethiopian Christians were effectively able to create a foundation for their faith within a completely new and previously non-Christian area.

Although we have briefly mentioned Mormonism during class discussion, we haven’t really explored the underlying beliefs of this religious system. Admittedly, before writing this blog I wasn’t completely familiar with the teachings of the Mormon church, but the information I found online was surprisingly similar to what we discussed about the Kebra Negast. Specifically, Mormons adhere to what is basically a reinterpretation of Judaism (specifically the Old Testament) that places one of the lost tribes of Israel in America. Mormons believe that they are all members of the House of Israel, and many of their names for cities/geographical locations (i.e. Nauvoo) are based on Hebrew names. The Mormons (often referred to as the Church of the Latter Day Saints) believe that Jesus also established a church in America (during the time of the Native Americans), but this church eventually failed. However, since Christ saw fit to establish a church in America, America itself is thus given meaning as a spiritual center, and Mormons believe that America will play a large roll in the events of the Last Days.

Both of these religions are essentially interpretations and elaborations upon previously existing religious systems (as many religions are). It is not my intent to criticize the validity of either the Mormon teachings, or the reading of the Kebra Negast that we studied in class. However, I find it extremely interesting to note that both these religions (Mormonism and Christians in Ethiopia) created stories that place themselves in direct relation to Israel, and at times they even relocate the spiritual center of their religion to their respective countries. This touches on one the key points of Rlst 100 that interest me the most: the ability of religions to adapt and reinterpret previously existing ideas to fit changing cultural and social patterns. By building off of strong previously existing religious institutions, both early Ethiopian Christians and Mormons were able to legitimize their religious beliefs and establish their homeland as a religious center.

Tuesday, May 13, 2008

The Kebra Negast as a way of establishing cultural and religious legitimacy

The purpose of this reading is essentially to establish a plausible story behind the claim that, “the Emperor of Ethiopia is the firstborn and eldest son of Solomon,” and the whole kingdom of the world (belonged) to the Emperor of Rom and the Emperor of Ethiopia” (16). This claim, albeit somewhat historically dubious, provides a strong basis for the establishment of a strong Ethiopian center for Christianity; a direct connection to a central figure of Christianity as well as a claim of historical power and possession creates a strong historical background for a group of individuals surrounded by other cultures and religions. Specifically, by establishing a lineage for the royalty of Ethiopia and linking this directly to King Solomon, the people of Ethiopia likely developed a stronger sense of meaning and solidarity.

This week’s prompt specifically asks us to identify how the Kebra Negast positions Ethiopia and creates value and status. In this passage, the Queen of Sheba (Ethiopia) meets with King Solomon and many remarks are made about her appreciation of his wisdom, beneficence, and eloquence (22, 24, etc.) Specifically, many references are made to King Solomon’s achievements, many of which are somewhat implausible; ships capable of flying through air and complete mastery of masonry, woodworking, and architecture- really? Even if these claims are somewhat inconceivable, they do show the presence of a “divine touch”, and this concept is nicely expressed by King Solomon himself when he notes that “this speech of mine springeth not from myself, but I give utterance only to what He maketh me to utter...He hath fashioned me in His own likeness and hath made me in His own image” (26). Although a direct reference to man’s creation by God is evidenced by these passages, it seems like King Solomon’s life has been particularly touched by God. However, for this influence to be spread to Ethiopia, a strong connection has to be made.

The most obvious way that the Kebra Negast accomplishes this is by establishing a lineage for the royalty of Ethiopia and connecting this to the decedents of King Solomon. The circumstances around the creation of the Queen of Sheba’s son, Menyelek, are fairly entertaining, although I’m not really sure if this aspect of the text was originally intended. Having a woman eat a lot of spicy food, tricking her into believing that she broke a promise so she can have a drink of water, and then having her release you from your promise not to “have your way with her”...and then having your way with her? Although King Solomon’s method of seduction was somewhat suspect, it certainly worked (as evidenced by Menyelek...the text specifically notes that the Queen of Sheba was a virgin). This son would grow up to be Emperor of Ethipia, and given his royal (and biblical) heritage, he would supposedly go on to do great things; as King Solomon noted earlier in the reading, “my children shall inherit the cities of the enemy, and shall destroy those who worship idols” (31). This connection is fundamental for establishing Ethiopia’s heritage and claim as a Christian center.

The Kebra Negast clearly draws connections between King Solomon and the royalty of Ethiopia, and this creates a strong sense of meaning and history for the Christian people of Ethiopia as a whole. Furthermore, many of the desirable traits of King Solomon seem to be present in Ethiopian royalty according to this text, as noted on pages 38-39. These traits, including most importantly the “divine touch” that I alluded to earlier, serve as a strong foundation for the legitimacy of both Ethiopia’s nobility and claims as a Christian center. By elaborating and reinterpreting a classical Christian story, the Christian people of Ethiopia have effectively constructed a strong national and religious identity for themselves.

Friday, May 9, 2008

Additional Post: Dr. Dino

I recently had a chance to watch a film that was previously shown to me in a high school AP Biology course. The movie is actually a compilation of a short series of lectures by Kent Hovind, an Evengelical minister who an outspoken proponent of theYoung Earth Creationist movement (for a good introduction to Kent Hovind’s teachings, go to http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KLCsd0MZaso). Kent Hovind, or Dr. Dino as he is commonly referred to, is well known in the scientific community for claiming that the world is less than 6,000 years old, and he also believes that humans and dinosaurs lived together (and indeed still do so today). For the purposes of this post and the overall nature of this blog, I don’t think it would be practical to analyze the validity of Kent Hovind’s arguments. However, I would like to present my thoughts and opinions on the nature of Kent Hovind’s rhetorical strategy in relation to some of our recent discussions in class.

In On Christian Teaching, Saint Augustine comments on the nature of rhetoric, specifically noting that it is a neutral discipline that can be used for the presentation of any idea, good or bad. I hadn’t previously considered this, and I found it particularly interesting and frightening; many times an audience will be pay more attention to the way a speaker presents ideas than the ideas themselves. In high school I was surprised that anyone could believe that the world is only 6,000 years old, that carbon dating is Satan’s creation, and that dinosaurs can still be found in various parts of the world today (all ideas supported by Hovind). However, after viewing Kent Hovind’s videos a second time, I realized that he is a charismatic and confident public speaker that is capable of constructing a seemingly feasible argument. It troubled me, probably much in the same way it troubled Saint Augustine, to see ideas and concepts distorted in this manner and then subsequently presented with an “air of factuality” that made them plausible and possibly even mutually exclusive. Although Kent Hovind’s teaching are supposedly Christian, they are derived from a somewhat narrow reading of the Bible.

Although Saint Augustine wrote On Christian Teaching well over 1500 years ago, I found it interesting that many of his thoughts on rhetorical strategies still apply today. In the specific case of Kent Hovind, radical interpretations of biblical scripture have attracted thousands of followers. Much of this success is likely due to Kent Hovind’s humorous, energetic, and seemingly informed style of speaking. Although Kent Hovind has been serving time in a federal prison since January 2007, he still has a large group of followers who distribute his DVD’s and propagate his ideas (see www.drdino.com). Perhaps Saint Augustine understood the power of a strong rhetorical strategy better than most; even after being convicted as a felon by the United States government, Kent Hovind is still able to influence the lives and thoughts of thousands of people.

Tuesday, May 6, 2008

Is this a thought, a post, a sentence, a list?

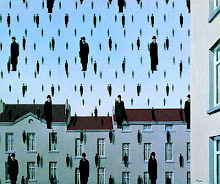

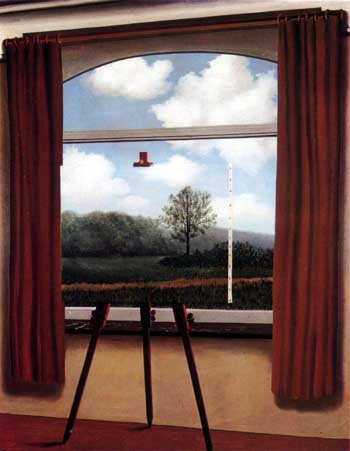

This week we are supposed to focus on a specific image with a religious theme or subject. Although a picture with obvious spiritual symbols would be easy and practical to analyze, I decided to focus on two paintings by Rene Magritte that have no specific religious affiliation. Both C’est Ne Pas Une Pipe and The Human Condition seem to comment on the difficulty of expressing one’s experience through a concrete human medium. Since pictures are essentially symbolic representations of the physical and the abstract, I thought it would be interesting to apply some of the concepts found in these paintings to the works we have discussed in class.

Both On Christian Teaching and the Psalms use symbolic imagery to convey ideas, and even The Indian Mounds of Wisconsin is comprised of symbolic representations of concepts (words are symbols, as Saint Augustine notes). However, symbols are simply a representation of one thing conveyed through the use of another. In essence, this is like a translation; the same meaning can be intended by the use of two separate words, even though the words themselves are different. This creates a problem, because as Theodore Sturgeon once said, “there are no true synonyms. There are no two words that mean exactly the same thing.” Sure, one can represent an idea or concept by using symbolic imagery or poetic language, but some connotations of the original concept will be, quite literally, lost in translation.

One can see this dilemma at the forefront of both of the two paintings that I selected. In C’est Ne Pas Une Pipe Magritte makes a bolt statement when he claims that a realistic looking picture of a pipe is not actually a pipe (literally, the words “translate” into “this is not a pipe”). However, the picture itself is obviously of a pipe, and it seems similar to a drawing that one would find in an advertisement or in an illustrated book. However, as Magritte subtly points out, even though thoughts of a pipe itself may be conjured up by staring at this “pipe”, the image is only a representation of the pipe itself. In no way does the picture of a pipe function as a pipe, and many aspects of the pipe are not conveyed by this two-dimensional representation. Essentially, this “pipe” that we perceive is simply a collection of pigment on a prepared surface that humans interpret as similar to another object that we experience in the physical world. Furthermore, even the association of the word “pipe” with various kinds of physical objects we perceive as pipes is as somewhat arbitrary designation. This separation between our existential experience and our ability to portray it is elaborated upon in , as Magritte presents a representation of a reality (a picture) that is partially constructed from a human representation of existence (a painting of the environment). Although our ability to represent our thoughts in a symbolic manner is an extremely important trait, and religion certainly couldn’t exist without it, but at the same time there are many dangers and shortcomings of symbolic representation.

To connect this to the material that we have been covering in class, sentient thought processes combined with the ability to construct symbolic representations of emotions, thoughts, and experiences have essentially enabled human society to flourish. At the same time, these symbols, although engaging and enjoyable (as Saint Augustine notes), are often incapable of conveying precise meanings, and often times the original concept is inaccurately or incompletely represented. Even with these shortcomings, symbols are really the only way to convey information to other people. With this in mind, I think it is fascinating that religions are capable of conveying such complex and profound ideas via symbols, although I wonder how much of the original concepts behind the religions have been preserved in their present form. I am not saying this is a necessary thing, as religions change and can interpreted in many ways (as symbols often are), but I think it would be interesting to compare the original ideas behind the formation of major world religions and their current interpretations by individuals.

Thursday, May 1, 2008

Symbology? Surely the word you are looking for is symbolism

My last post focused on Saint Augustine’s perspective for approaching a translated work, and last week I commented on the analogies found in the Psalms. Since both of these concepts (and indeed, even the posts) are symbolic in nature, I think it would be prudent to also examine Saint Augustine’s thoughts on the nature and purpose of symbols. As I noted in my last post, Saint Augustine rightly believes that language is just a symbolic representation of human thought. Thus, the words themselves are only important because they can help the individual understand the concept that is trying to be conveyed.

Humans often give meaningless things symbolic purpose, and Saint Augustine does not have any major qualms with this. For example, letters are simply marks that only contain meaning because we have an established system for interpreting them. Thus, Saint Augustine believes that if we use these symbols to understand the important concepts (the nature of God, and one’s development of love and reverence for Him), then symbols can be an extremely helpful and beneficial thing (30). However, Saint Augustine sees a potential problem if the importance of the symbol overrides the significance of the original abstraction that it is attempting to represent (74). Rather, Saint Augustine believes we should know that, “Someone who attends to and worships a thing which is meaningful but remains unaware of its meaning is a slave to a sign. But the person who...worships a useful sign...does not worship a thing which is only apparent and transitory but rather the thing to which all such things are to be related. Such a person is spiritually free” (75). Thus, we are to direct our attention to the symbolic understanding of God, but they symbols themselves are only important because they help us conceptualize the concepts behind His existence.

This is a valid argument, and it is one that can be applied to more than just the study of God. I feel that one should approach Saint Augustine’s work and the book of Psalms For with the mindset that it is not necessarily the words that are of paramount importance. Really, the words are just a representation, often removed several times due to translation and copying errors, of ideas that were formed using difference conceptual frameworks. If we can sort through the difficulties presented by this and get to the heart of the matter, the ideas that inspired these works and the subsequent interpretations and applications of the underlying concepts, I feel that much more can be gained from these older texts. Similar to how Saint Augustine thought that symbols might be a better way to convey complex qualitative abstractions with symbols, perhaps the best way to approach these texts is by using our own conceptual frameworks (not that we have much or a choice) to explore the intriguing ideas and problems presented by both On Christian Teaching and the book of Psalms. We are students at a private liberal arts college that encourages the development of critical thinking, and a large part of this so-called intellect supposedly relates to the interpretation of and expression of alternative perspectives. Thus, we should be able to figure out the symbology of this work without much problem.

Tuesday, April 29, 2008

On Translated Works

Saint Augustine’s thoughts on the difficulties of translation, as posed in his work, On Christian Teaching, struck me as particularly interesting. Before reading Book II, I did some background research and discovered that Saint Augustine wrote all of his in Latin. To read the translated words of Saint Augustine’s thoughts on the difficulties of translation was interesting indeed, but I found that his thoughts on the symbolic nature of language and translation were much more intriguing.

Specifically, Saint Augustine views language as a system of symbols, both written and verbal, that represent both the material and the intangible. According to Saint Augustine, it is not so much the language itself that is important, but the ideas that the language is attempting to convey (40). Thus, Augustine is less concerned with the rules of language than he is the meaning of the thoughts that are being conveyed (41). Augustine later goes on to emphasize that learning and exploring the intricacies behind languages should really only be explored as a way of furthering one’s knowledge and understanding of the greater Truths (54). It is precisely this alteration of meaning that bothers Saint Augustine when one is exploring a translated work; inexperienced translators (and sometimes even well-versed scholars) can lose some or all of the originally intended meaning behind a passage when they translate it. With this in mind, a translation that works best takes culturally significant information into account and attempts to get to the root of the original meaning.

This perspective is particularly useful when looking at the Psalms, as many of the Psalms contain phrases or references that are not familiar to our cultural sensibilities, or may not have cultural equivalents for our society. For example, in Psalm 37 Alter notes that the simile of wicked men and the withering of grass is best understood with the knowledge that Israel has a growing season that was followed by an extremely dry hot season (killing most vegetation with dispatch). While we as American’s (specifically Wisconsinites) don’t have a perception of grass as a quickly dying plant that withers under the hot sun, we can better understand this specific simile once we understand the meaning behind the original words. Without these culturally significant pieces of information, one can easily miss the intended meaning (what Saint Augustine considers to be most important in a text) behind a word or a phrase. By paying close attention to the cultural background and intended meaning (often a word has more than one meaning in a given situation), one can better understand translated texts. In particular, I found the footnotes to be indispensable when I was reading the Psalms; I understood much more after the additional information behind the words was presented. With this in mind, while translated works are often difficult to fully understand, they can convey the same ideas that the original text did, but simply do so in a different manner. With this in mind, I think it would be interesting to see if Saint Augustine’s ideas were translated in a manner that encapsulates the essence of his original ideas.

Saturday, April 26, 2008

Additional Post: Male Circumcision Lecture

This last Wednesday I had the opportunity to attend a talk by Professor Robert Bailey. Professor Bailey spoke about the benefits of circumcision for HIV/AIDS prevention, but he also spent a fair amount of time talking about the religious and cultural significance of this practice. I found it particularly interesting that Professor Bailey decided to elaborate on the interconnectedness of a specific religious tradition and its practical health benefits.

During his lecture, Professor Bailey stressed that circumcision has been around for a long period of time, and that it predates the formal foundation of both Judaism and Islam. However, male circumcision is a extremely important tradition in both of these cultures. Although circumcision may be done for aesthetic or personal reasons, it also offers many potential health benefits. Specifically, male circumcision allows for the keratinization of the inner mucosal membrane of the foreskin (which is prone to inflammation and infection).

Apparently, circumcision is practically a necessity for people living in sandy desert climates. Professor Bailey noted that during the first World War, over 170,000 American troops were hospitalized with serious infections that were caused by particles of sand trapped under the foreskin. After these troops returned home, male circumcision became commonplace in America (in areas like the Midwest, approximately 90% of all men are circumcised). In this way, a beneficial medical procedure became medically and culturally commonplace.

Similarly, it is thought that the religions of Judaism and Islam adopted the previously existing procedure of circumcision and turned it into a rite of passage. Specifically, in the religion of Judaism, male circumcision is now supposed to be an outward symbolic representation of the eternal covenant between God and all Jewish people. I find this particularly interesting, as one generally wouldn’t associate a specific medical procedure with a religion. However, in terms of fostering a group identity, I can hardly think of a more personal form of body modification that is shared by a group of people. This certainly relates to the ability of religions to adopt beneficial practices and change over time; by imbuing a necessary and beneficial medical procedure with religious meaning, both Judaism and Islam ensure health and a stronger sense of community.

During his lecture, Professor Bailey stressed that circumcision has been around for a long period of time, and that it predates the formal foundation of both Judaism and Islam. However, male circumcision is a extremely important tradition in both of these cultures. Although circumcision may be done for aesthetic or personal reasons, it also offers many potential health benefits. Specifically, male circumcision allows for the keratinization of the inner mucosal membrane of the foreskin (which is prone to inflammation and infection).

Apparently, circumcision is practically a necessity for people living in sandy desert climates. Professor Bailey noted that during the first World War, over 170,000 American troops were hospitalized with serious infections that were caused by particles of sand trapped under the foreskin. After these troops returned home, male circumcision became commonplace in America (in areas like the Midwest, approximately 90% of all men are circumcised). In this way, a beneficial medical procedure became medically and culturally commonplace.

Similarly, it is thought that the religions of Judaism and Islam adopted the previously existing procedure of circumcision and turned it into a rite of passage. Specifically, in the religion of Judaism, male circumcision is now supposed to be an outward symbolic representation of the eternal covenant between God and all Jewish people. I find this particularly interesting, as one generally wouldn’t associate a specific medical procedure with a religion. However, in terms of fostering a group identity, I can hardly think of a more personal form of body modification that is shared by a group of people. This certainly relates to the ability of religions to adopt beneficial practices and change over time; by imbuing a necessary and beneficial medical procedure with religious meaning, both Judaism and Islam ensure health and a stronger sense of community.

Thursday, April 24, 2008

Analogies in the Psalms

Earlier this year I wrote a paper that focused on the disadvantages of using metaphors and similes in scientific writing. To briefly summarize my argument, I feel that analogies, although engaging, can divert attention from the core principles of a theory. Furthermore, analogies can be downright distracting. However, one of the things that struck me most as I was reading the book of Psalms was the artistic use of metaphor and language to describe intense religious emotions and experiences. Many of these analogies reminded me of the works that we studied earlier this year in Freshman Studies (particularly Chaung Tzu), and I would like to do a more thorough examination of the purpose and function of the analogies in the book of Psalms.

The first Psalm contains a simple yet elegant simile: “And he shall be like a tree planted by streams of water, that bears its fruits in its season, and its leaf does not wither- and in all that he does he prospers. Not so the wicked, but like chaff that the wind drives away” (4). This imagery of one seed being guided by a river to a favorable destiny as opposed to a solitary seed being battered around in a hostile environment directly connects to the underlying ethic found in the Psalms; one cannot survive without the guidance and beneficence of the LORD (YHWH), and those who discard their beliefs will be subject to the cruelties of the world.

Another analogy that struck me as particularly powerful is found in Psalm 42: “As a deer yearns for streams of water, so I yearn for You, O God” (148). This simple sentence conveys the intense desire and primal thirst that man feels for god; the god-shaped vacuum that I mentioned earlier this year. Similarly, the seemingly unfair prosperity of evildoers is explained by Psalm 37: “Do not be incensed by evildoers. Do not envy those who do wrong. For like grass they will quickly wither and like green grass they will fade.” Simply saying that bad people will eventually get their comeuppance is not as strong as the visual imagery of seemingly-flourishing grass quickly dying and losing all of its attractive color.

The purpose that these analogies serve is simultaneously simple and complex. On a baser level, they are generally quite appealing and beautiful; I was initially drawn to these specific lines because of their engaging traits. Indeed, this is one of the main reasons that I feel metaphors are not as appropriate in scientific texts. However, the analogies found in the book of Psalms also express human emotion and qualitative aspects of life in a way that would otherwise be difficult or impossible. One cannot quantize a desire for God in a consistent manner; every individual’s experience and perception is different. However, by using elegant analogies, the authors of the Psalms express abstract human emotion and thought in a way that is much more accessible and engaging than any other method that comes to my mind. Much like the analogies found in Chuang Tzu’s Basic Writing, I feel that the analogies in the book of Psalms strengthens the overall text and makes it more accessible.

The first Psalm contains a simple yet elegant simile: “And he shall be like a tree planted by streams of water, that bears its fruits in its season, and its leaf does not wither- and in all that he does he prospers. Not so the wicked, but like chaff that the wind drives away” (4). This imagery of one seed being guided by a river to a favorable destiny as opposed to a solitary seed being battered around in a hostile environment directly connects to the underlying ethic found in the Psalms; one cannot survive without the guidance and beneficence of the LORD (YHWH), and those who discard their beliefs will be subject to the cruelties of the world.

Another analogy that struck me as particularly powerful is found in Psalm 42: “As a deer yearns for streams of water, so I yearn for You, O God” (148). This simple sentence conveys the intense desire and primal thirst that man feels for god; the god-shaped vacuum that I mentioned earlier this year. Similarly, the seemingly unfair prosperity of evildoers is explained by Psalm 37: “Do not be incensed by evildoers. Do not envy those who do wrong. For like grass they will quickly wither and like green grass they will fade.” Simply saying that bad people will eventually get their comeuppance is not as strong as the visual imagery of seemingly-flourishing grass quickly dying and losing all of its attractive color.

The purpose that these analogies serve is simultaneously simple and complex. On a baser level, they are generally quite appealing and beautiful; I was initially drawn to these specific lines because of their engaging traits. Indeed, this is one of the main reasons that I feel metaphors are not as appropriate in scientific texts. However, the analogies found in the book of Psalms also express human emotion and qualitative aspects of life in a way that would otherwise be difficult or impossible. One cannot quantize a desire for God in a consistent manner; every individual’s experience and perception is different. However, by using elegant analogies, the authors of the Psalms express abstract human emotion and thought in a way that is much more accessible and engaging than any other method that comes to my mind. Much like the analogies found in Chuang Tzu’s Basic Writing, I feel that the analogies in the book of Psalms strengthens the overall text and makes it more accessible.

Tuesday, April 22, 2008

The Ethical Stance of the Psalms

At first glance, Alter’s translation of The Book of Psalms does not appear to focus intently on the traditional ethical code that most individuals associate with Christianity. No lists of prescriptive rules are found in the text, and references to specific sins are few and far between. However, there is an interesting perspective of appropriate ethical action that underlies the majority of The Book of Psalms, and this ethical stance focuses primarily on piety and accountability for one’s actions.

One does not have to look far to see the basis of this ethical philosophy. Psalm I clearly states that “the wicked will not stand up in judgment, nor offenders in the band of the righteous. For the lord embraces the way of the righteous, and the way of the wicked is lost” (4). Essentially, the LORD will judge and punish individuals who are not just, but he will reward and protect those who are righteous. There is a certain immediacy to this judgement and punishment that we talked about in class, and this can be seen in Psalm 86 when the author notes that “The LORD indeed will grant bounty...Justice before Him goes, that He set His footsteps on the way” (302). This trend of seeing justice as the preferable action to dishonesty and corruption, and the direct consequences of one’s actions in this world is repeated throughout the Psalms.

As an extension of this concept, simply being a just individual is not enough to gain the LORD’s favor according to the Psalms; one must worship the LORD dutifully and live one’s life in a pious manner. According the Psalm 30, one should “Hymn to the LORD...acclaim his holy name” (102). Essentially, one must act justly towards one’s fellow man; to fall in the LORD’s good graces one must dutifully worship the God of Israel (YHWH).

These prescriptive ethical codes of action contained in the Psalms seem unlike the current model associated with Christianity and Judaism. Unlike many religions, the book of Psalms seem primarily concerned with the importance of actions and beliefs in this world and the immediacy of the subsequent consequences. Some specific recommendations of action are given in the book of Psalms, but they are fairly general. For example, the author of Psalm 7 writes that “one spawns wrongdoing, grows big with mischief, gives birth to lies. A pit he delved, and dug it, and he fell in the trap he made” (20). Although some direct recommendations are made in the Psalms (do not lie, steal, or be mischievous), generally the code of action endorsed is assumed to be already known by the religious follower. This forces the individual to assume that all actions are being scrutinized and that one must always do what one considers just. This seems like a livable ethic, but at the same time it would be one that would completely pervade all aspects of one’s life. Although the specific rewards and punishments associated with an afterlife seem to be missing from this ethical code, the potential for divine intervention (especially vengeful punishment) would probably make an ethical code like this quite successful. I personally couldn’t see myself living under that sort of scrutiny, but given a different cultural environment I can see how this ethical code might potentially strengthen my sense of identity or group belonging.

One does not have to look far to see the basis of this ethical philosophy. Psalm I clearly states that “the wicked will not stand up in judgment, nor offenders in the band of the righteous. For the lord embraces the way of the righteous, and the way of the wicked is lost” (4). Essentially, the LORD will judge and punish individuals who are not just, but he will reward and protect those who are righteous. There is a certain immediacy to this judgement and punishment that we talked about in class, and this can be seen in Psalm 86 when the author notes that “The LORD indeed will grant bounty...Justice before Him goes, that He set His footsteps on the way” (302). This trend of seeing justice as the preferable action to dishonesty and corruption, and the direct consequences of one’s actions in this world is repeated throughout the Psalms.

As an extension of this concept, simply being a just individual is not enough to gain the LORD’s favor according to the Psalms; one must worship the LORD dutifully and live one’s life in a pious manner. According the Psalm 30, one should “Hymn to the LORD...acclaim his holy name” (102). Essentially, one must act justly towards one’s fellow man; to fall in the LORD’s good graces one must dutifully worship the God of Israel (YHWH).

These prescriptive ethical codes of action contained in the Psalms seem unlike the current model associated with Christianity and Judaism. Unlike many religions, the book of Psalms seem primarily concerned with the importance of actions and beliefs in this world and the immediacy of the subsequent consequences. Some specific recommendations of action are given in the book of Psalms, but they are fairly general. For example, the author of Psalm 7 writes that “one spawns wrongdoing, grows big with mischief, gives birth to lies. A pit he delved, and dug it, and he fell in the trap he made” (20). Although some direct recommendations are made in the Psalms (do not lie, steal, or be mischievous), generally the code of action endorsed is assumed to be already known by the religious follower. This forces the individual to assume that all actions are being scrutinized and that one must always do what one considers just. This seems like a livable ethic, but at the same time it would be one that would completely pervade all aspects of one’s life. Although the specific rewards and punishments associated with an afterlife seem to be missing from this ethical code, the potential for divine intervention (especially vengeful punishment) would probably make an ethical code like this quite successful. I personally couldn’t see myself living under that sort of scrutiny, but given a different cultural environment I can see how this ethical code might potentially strengthen my sense of identity or group belonging.

Friday, April 18, 2008

Religious Changes as a Result of Culture

Today in class we talked about the interplay between spirituality and culture that we observed in Alter’s The Book of Psalms. In a few of my previous blog posts I mentioned various ways that religion affects cultural perceptions and social structure, but I skimmed over the instances in which religion is influenced by environmental (cultural/socioeconomic) pressures. Specifically, in my last post I mentioned that the same religious ideas can be interpreted in numerous ways as cultures change and shift perspectives. However, I would like to use this post to comment on some of my personal observations regarding the changes that culture can elicit in a religion.

This post was prompted by an article that I read earlier this year (found here). To briefly summarize, the Vatican recently released a list of actions that are now considered sinful behavior for adherents of the Catholic faith. These sins include polluting the environment and some forms of genetic manipulation. This is quite a stretch from the original seven deadly sins of lust, gluttony, greed, sloth, wrath, envy, and pride. However, as the article states, “the Vatican says it is time to modernize the list to fit a global world.”

This abrupt change is quite interesting, because before I took Rlst 100 I did not anticipate that religions would change their fundamental doctrines to function more effectively. However, if religion is a dynamic system that allows people to interpret and give meaning to their existence, it makes sense that religion can and should change to fit the environment in which it is practiced. The true nature of religion, the interpretation and usage of idea (not the ideas themselves), is readily apparent when one looks at religion this way; people are sometimes willing to change their religion as it becomes necessary.

Although it seems counterintuitive to change the traditions and regulations that have operated effectively for such a long period of time, it is this change that is partly responsible for the longevity of certain religions. If religions were static institutions they would quickly become obsolete, because society readily develops new technologies and perspectives for interacting with the world. For example, several years ago when inoculations for chickenpox were becoming available, there was some concern that the vaccines were tested using human embryos. This was a clear violation of Roman Catholic doctrine of the time, as research on human embryos was considered immoral, and “the tainted tree bears tainted fruits.” However, the church made an exception, because the good that could come out of inoculating infants outweighed the moral contradiction in Catholic law. It is changes like these that allow religion to adapt to the ever-evolving cultural climate, and this, in part, is why various religions have been so successful at spreading and maintaining a global presence.

This post was prompted by an article that I read earlier this year (found here). To briefly summarize, the Vatican recently released a list of actions that are now considered sinful behavior for adherents of the Catholic faith. These sins include polluting the environment and some forms of genetic manipulation. This is quite a stretch from the original seven deadly sins of lust, gluttony, greed, sloth, wrath, envy, and pride. However, as the article states, “the Vatican says it is time to modernize the list to fit a global world.”

This abrupt change is quite interesting, because before I took Rlst 100 I did not anticipate that religions would change their fundamental doctrines to function more effectively. However, if religion is a dynamic system that allows people to interpret and give meaning to their existence, it makes sense that religion can and should change to fit the environment in which it is practiced. The true nature of religion, the interpretation and usage of idea (not the ideas themselves), is readily apparent when one looks at religion this way; people are sometimes willing to change their religion as it becomes necessary.

Although it seems counterintuitive to change the traditions and regulations that have operated effectively for such a long period of time, it is this change that is partly responsible for the longevity of certain religions. If religions were static institutions they would quickly become obsolete, because society readily develops new technologies and perspectives for interacting with the world. For example, several years ago when inoculations for chickenpox were becoming available, there was some concern that the vaccines were tested using human embryos. This was a clear violation of Roman Catholic doctrine of the time, as research on human embryos was considered immoral, and “the tainted tree bears tainted fruits.” However, the church made an exception, because the good that could come out of inoculating infants outweighed the moral contradiction in Catholic law. It is changes like these that allow religion to adapt to the ever-evolving cultural climate, and this, in part, is why various religions have been so successful at spreading and maintaining a global presence.

Tuesday, April 15, 2008

Comparison of Different Translations of Psalm II

The most readily apparent difference between Alter’s translation and the Bay Psalm Book’s version of Psalm II is the metrical organization and diction. Although these two aspects of the Psalms are seemingly less important than the actual content, the changes in metrical structure and diction shift the emphasis of the Psalm itself and imbue it with alternative meaning. It is appropriate to note that both the Bay Psalm Book and Alter’s The Book of Psalms are translations that were created during different time periods in different cultures. As such, the translators of these works likely had different perspectives (lenses) through which they saw the world, and these effects are clearly seen in both of these translations.

The first aspect that I would like to focus on is the metrical organization of Psalm II in the Bay Psalm Book and Alter’s The Book of Psalms. Alter specifically chooses not to have a rigidly defined meter in his translation, as the original Hebrew texts have no such structure (xxi). However, the Bay Psalm Book has a defined metrical structure; the first and third lines contain eight syllables, while the second and fourth contain six (this pattern continues throughout the Psalm). The translators of the Bay Psalm Book omitted words in some places and added them in others to create this structure, but Alter chooses to stick with the most literal translation, claiming that the significant content is generally found within the Hebrew poetic style of parallelism (xxi).

Another interesting aspect of these two translations of Psalm II is the translators’ diction. For example, in the Bay Psalm Book the translators choose the words furiously, rage, and heathen. However, Alter simply uses the word aroused and substitutes nation for heathen. Throughout Psalm II, the language of the Bay Psalm Book is much more personal and intense, while Alter’s translation seems much more political, almost like a motivational speech. Furthermore, every other line of the Bay Psalm Book rhymes with another line (either two lines before or after it). For example, lines 12 and 10 rhyme suddenly/he, and lines 22 and 24 rhyme abroad/rod. This choice of words forced the Bay Psalm Book translators to rearrange sentences and this in turn shifted focus away from the parallel sentence structure.

The differences between these translations can probably be explained by an examination of the different perspectives that influenced the translations themselves. As Alter note in his foreword, he is particularly interested in preserving the original parallel structure and removing the distracting references, especially the ones with significant cultural baggage attached. Writing from this academic tone, it seems like Alter views Psalm II as more of a political call to arms than a personal expression of desire for help when one is surrounded by non-believers (he uses the word nation instead of heathens). However, the Bay Psalm Book appears to be much less concerned with an accurate representation of the original Hebrew text. In contrast to Alter’s translation, the Bay Psalm Book is much more accessible and applicable on an individual level; one could easily imagine a newly-arrived pilgrim praying for guidance as he/she stands surrounded by a land of so-called “heathens”. This use of the same religious ideas (the original Hebrew text) in different cultural contexts emphasizes the importance of the consideration of different perspectives when thinking about religion. Essentially, these different perspectives shifted the meaning of the Psalms to suit the cultural/social environment of the early Pilgrims and Alter, but this is certainly not the only place where this concept can be seen. Much like the Indian mounds of Wisconsin, similar original ideas were interpreted and used by different people in different manners as culture and society required it.

The first aspect that I would like to focus on is the metrical organization of Psalm II in the Bay Psalm Book and Alter’s The Book of Psalms. Alter specifically chooses not to have a rigidly defined meter in his translation, as the original Hebrew texts have no such structure (xxi). However, the Bay Psalm Book has a defined metrical structure; the first and third lines contain eight syllables, while the second and fourth contain six (this pattern continues throughout the Psalm). The translators of the Bay Psalm Book omitted words in some places and added them in others to create this structure, but Alter chooses to stick with the most literal translation, claiming that the significant content is generally found within the Hebrew poetic style of parallelism (xxi).

Another interesting aspect of these two translations of Psalm II is the translators’ diction. For example, in the Bay Psalm Book the translators choose the words furiously, rage, and heathen. However, Alter simply uses the word aroused and substitutes nation for heathen. Throughout Psalm II, the language of the Bay Psalm Book is much more personal and intense, while Alter’s translation seems much more political, almost like a motivational speech. Furthermore, every other line of the Bay Psalm Book rhymes with another line (either two lines before or after it). For example, lines 12 and 10 rhyme suddenly/he, and lines 22 and 24 rhyme abroad/rod. This choice of words forced the Bay Psalm Book translators to rearrange sentences and this in turn shifted focus away from the parallel sentence structure.

The differences between these translations can probably be explained by an examination of the different perspectives that influenced the translations themselves. As Alter note in his foreword, he is particularly interested in preserving the original parallel structure and removing the distracting references, especially the ones with significant cultural baggage attached. Writing from this academic tone, it seems like Alter views Psalm II as more of a political call to arms than a personal expression of desire for help when one is surrounded by non-believers (he uses the word nation instead of heathens). However, the Bay Psalm Book appears to be much less concerned with an accurate representation of the original Hebrew text. In contrast to Alter’s translation, the Bay Psalm Book is much more accessible and applicable on an individual level; one could easily imagine a newly-arrived pilgrim praying for guidance as he/she stands surrounded by a land of so-called “heathens”. This use of the same religious ideas (the original Hebrew text) in different cultural contexts emphasizes the importance of the consideration of different perspectives when thinking about religion. Essentially, these different perspectives shifted the meaning of the Psalms to suit the cultural/social environment of the early Pilgrims and Alter, but this is certainly not the only place where this concept can be seen. Much like the Indian mounds of Wisconsin, similar original ideas were interpreted and used by different people in different manners as culture and society required it.

Wednesday, April 9, 2008

Effects of Religion on Social Structure

Near the end of class today we started to talk about the possible functions of the Indian mounds found in Wisconsin. Although we discussed many potential uses and purposes of these mounds, the only solid conclusion we came to was that the function of the mounds changed over time. Similarly, Birmingham and Eisenberg do not give a singular answer, but instead suggest that the mounds held different purposes and meaning for different people (141). The societal function of the mounds changed over time, and eventually the ceremonial building of mounds stopped when culture no longer required it. One of these purposes that we briefly mentioned in class is the clear definition of social groups and the potential establishment of hierarchical social systems.

In the Paleo-Indian and Archaic time periods most of the mounds were conical and burials were done with many individuals (77). As time progressed and effigy mounds became more frequent, the function of the mounds as burial sites decreased significantly, and many mounds contained no bodies at all (127). Finally, as culture changed and social patterns shifted, the emergence of Mississippian temple mounds and more extravagant burials like the “princess” mound became more prevalent (147, 159). This progression makes sense; the change from disorganized nomadic living to more established social centers was accompanied by an increase in social stratification and the symbolic representation of this newly-created system. Also, as population centers increased in size, the creation of larger and more elaborate mounds was possible. Birmingham and Eisenberg state that “the effigy mound ceremonial helped bind people together...forming a new horticulturally based social confederation with distinct clan structures organized into upper and lower divisions” (141). The mounds, although probably not originally meant as a social indicator (for individuals or communities), became a representation the Native American’s early social structure. However, these mounds influenced societies as much as they represented them; the immense earthenworks brought together large groups of people and provided a strong physical reaffirmation of the “order of existence” that was generally accepted at the time.

Similar interplay between religion and social structure can be seen today. At first glance, the United States does not seem to have social segregation based on religious affiliation. However, a brief look at the political world shows major disparities in religious representation (1.7% of the USA is Episcopalian, but 15.4% of all presidents have been Episcopalian). Similarly, the current religious composition of the United States Congress is non-representative of the general population- there is not a single individual who openly claims to be an atheist! If nothing else, religion seems to play a large part in how we view our social leaders. The caste system of India is an even better example of the religious influences on the creation and mediation of social structures; people are born into, work in, live in, marry in, and die in religiously affiliated groups (see diagram below for visual representation). Overall, I feel like the connection between culture and religion is strong, but it is interesting that religion can affect cultural and social patterns as much as be an expression of them.

In the Paleo-Indian and Archaic time periods most of the mounds were conical and burials were done with many individuals (77). As time progressed and effigy mounds became more frequent, the function of the mounds as burial sites decreased significantly, and many mounds contained no bodies at all (127). Finally, as culture changed and social patterns shifted, the emergence of Mississippian temple mounds and more extravagant burials like the “princess” mound became more prevalent (147, 159). This progression makes sense; the change from disorganized nomadic living to more established social centers was accompanied by an increase in social stratification and the symbolic representation of this newly-created system. Also, as population centers increased in size, the creation of larger and more elaborate mounds was possible. Birmingham and Eisenberg state that “the effigy mound ceremonial helped bind people together...forming a new horticulturally based social confederation with distinct clan structures organized into upper and lower divisions” (141). The mounds, although probably not originally meant as a social indicator (for individuals or communities), became a representation the Native American’s early social structure. However, these mounds influenced societies as much as they represented them; the immense earthenworks brought together large groups of people and provided a strong physical reaffirmation of the “order of existence” that was generally accepted at the time.

Similar interplay between religion and social structure can be seen today. At first glance, the United States does not seem to have social segregation based on religious affiliation. However, a brief look at the political world shows major disparities in religious representation (1.7% of the USA is Episcopalian, but 15.4% of all presidents have been Episcopalian). Similarly, the current religious composition of the United States Congress is non-representative of the general population- there is not a single individual who openly claims to be an atheist! If nothing else, religion seems to play a large part in how we view our social leaders. The caste system of India is an even better example of the religious influences on the creation and mediation of social structures; people are born into, work in, live in, marry in, and die in religiously affiliated groups (see diagram below for visual representation). Overall, I feel like the connection between culture and religion is strong, but it is interesting that religion can affect cultural and social patterns as much as be an expression of them.

Tuesday, April 8, 2008

Religious and Symbolic Significance of Various Animal Representations

Blog Question #2: Were the animal-shaped mounds of Wisconsin different from the animal representations in Lascaux Cave or the animals in the name of sport clubs (i.e. Chicago Bears)? What might be the religious significance of these representations of animals, thinking in terms of our own definition of religion?

Although the artistic media are different, the animal-shaped effigy mounds of Wisconsin and the cave paintings of Lascaux share many common traits with modern animal symbolism. First and foremost, a symbol is simply one thing used to represent another thing. The Lascaux cave paintings, the mounds of Wisconsin, and even the modern-day animal symbols of sports teams have undeniable symbolic meaning, but the religious significance of these things are somewhat more evasive.

Before I examine the similarities and differences between various animal representations, I should make my position on the importance of symbols known. I don’t think it is the nature of the symbol itself that is most significant, but rather the interpretations and uses of the symbol. For example, focusing on the physical differences between a peace symbol printed on a shirt and a similar symbol on a belt buckle will not be as revealing as an examination of what the symbol has meant to different people over the last half-century. It is the interpretations and uses of the symbol that are most important.